The History: A Woman, a Pioneer, and Prussian Blue

In the days of the first photographs, around 1839, pioneers of this field who integrated science and art began to emerge and take their place in the history of photography. During this era the thought of color photography in the contemporary sense was not even in the minds of the ingenious inventors.

However, one color did manage to make its mark through the hands of a woman born in 1799 named Anna Atkins. She is marked with being the first to publish a book of photographs and one of the first female photographers. [1]

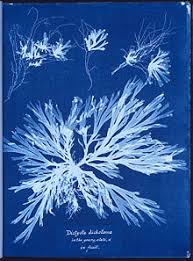

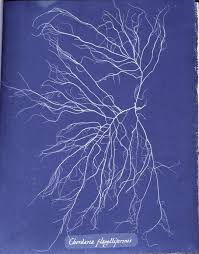

Figure 1. Anna Atkins, Untitled, Cyanotype Photograms, 1843-1853, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions.

The vivid Prussian blue images that you see above are one of the 425 photographs published by Atkins. It is called a cyanotype. The name cyanotype was derived from the Greek word cyan, meaning “dark-blue impression”.

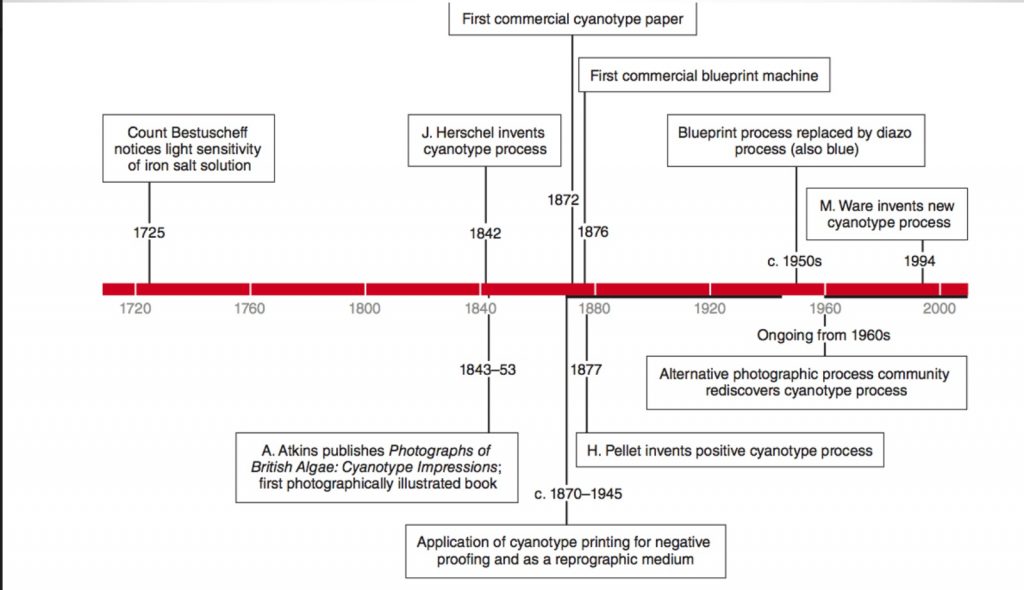

The astronomer and chemist John Fredrick William Herschel invented this process in 1842. There were even earlier contributors to this process that made Herschel’s finalized photographic quality possible. The color changes that happen in iron salts were discovered and documented by Count Bestuscheff in 1725 and further researched in 1831 by Johann Wolfgang Doebereiner. Finally the bright Prussian blue was prepared based off the previous research by Heinrich Diesbach in Berlin between 1704 and 1710.[2]

Herschel experimented with the cyanotype process and inspired the pioneer Anna Atkins. Atkins father was Dr. John Children, a mineralist, zoologist, and chemist. Her mother died from childbirth complications shorty after Atkins was born. Being the only child, Atkins grew to be very educated and went into the field of botany. Anna married John Pelly Atkins in 1825, she then devoted herself to collecting plants and documenting them using this process.

Anna was satisfied with the accuracy of the prints, which could be challenging. “The difficulty of making accurate drawings of objects as minute as many of the Algae and Confera, has induced me to avail myself of Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of Cyanotype, to obtain impressions of the plants themselves.”[3]

Anna Atkins went on to publish a book with three volumes titled Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype impressions. This was officially the first book published with photographs. [4]

Since Anna Atkins prolific work, the cyanotype process was not used extensively. It was only of merit for engineers and architects during the 1880’s to provide proofs for their plans. The first commercial cyanotype paper was produced in France around 1872. Students were often instructed in the cyanotype process for creating what we no we now call a ‘blueprint’ for technological designs. Finally the first blueprint press was made in Switzerland and introduced to the United States in 1876. [5]

Figure 2. Timeline of cyanotype process, Provided by L. Powell.

The Process: A Cyanotype

Currently the cyanotype is considered an alternative photographic process. Kits to make cyanotypes are readily available through most photographic supply stores. The process involves two chemicals, the first is called potassium ferricyanide and the second is ferric ammonium citrate (green).[6] These two chemicals are iron and iron salts that react with the potassium (another form of iron) creating the vivid blue complex.

You can buy the chemicals and use them on anything from watercolor paper to fabric OR you can buy the premade paper. Here are some affiliate link options:

If you choose traditional chemicals:

The chemicals are mixed and wiped or applied with a regular paint brush onto paper in a dark room. The light sensitive solution must then dry for a few minutes in total darkness.

Once dry, flat objects or a negative may be placed on the paper and it is then exposed to UV light. I recommend large transparencies for negatives or choose objects like Anna Atkins.

If you do this outside, you know you are done when you have a distinct opposite outline around your object.

After a proper exposure time, which can only be determined by the amount of sunlight the image must then be washed with a distilled water bath for at least a minute to intensify the blue.

If you want to really intensify the blue, sprinkle the paper with some hydrogen peroxide. Then, hang it to dry.[8]

If you try Pre Treated Paper:

These are often marketed as a kids education activity. I have used outside and in a darkroom successfully, but you will need bright light and a longer exposure time. This is a challenge in my environment most of time.

My first attempts were a failure to say the least. I found some flat objects, leaves and branches and carefully arranged them on the sheet. Then I found a small stream of sunlight in the backyard and left my first print for the instructed 3-5 minutes.

After rinsing the paper I could tell no exposure had been made due to lack of time and sunlight.

My next attempt included the same process and configuration of items and I left my sheet outside for 5 hours, just to see. A faint and faded imprint began to appear on the paper after rinsing.

Conclusion 1 in creative process: The Northwest is not cyanotype friendly. Who knew when I would see the sun next?

Conclusion 2 in creative process: Anna Atkins must have been darn good.

Next step meant I tried new paper, (linked above) waited for FULL SUN AND I also decided to make digital negatives of my own photographs in Photoshop and print them onto transparencies. Here is an example of the results.

Fake it till you make it! Make a cyanotype on your phone.

Download Aviary and follow the video below to make some with your phone photos.

HINT: Starting with a Black and White image works best I have found. You can do this in Filmborn or Snapseed prior to making the “Cyanotype” as in the video.

Share your cyanotype experiments and tag me!

Bibliography [1] Naomi Rosenblum, A world history of photography. Third Edition ed. New York, N.Y.: Abbeville Press, 1984. [2] L. Powell, (1991). Cyanotype - color it blue. PSA Journal, 57(6), 20+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA10888373&v=2.1&u=marylhuniv&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=883d1f4a640681052e83afdaffc8f9db. [3] "Anna Atkins (Getty Museum)." Anna Atkins (Getty Museum). http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artMakerDetails?maker=1542&page=1 (accessed January 10, 2014). [4] Kat McDaniel, "synkroniciti." synkroniciti. http://synkroniciti.com/2013/09/26/prussian-blue-and-early-photography-following-synchronicity-from-diesbach-to-anna-atkins/ (accessed January 10, 2014). [5] L. Powell, (1991). Cyanotype - color it blue. PSA Journal, 57(6), 20+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA10888373&v=2.1&u=marylhuniv&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=883d1f4a640681052e83afdaffc8f9db. [6] Armstrong, Carol, and M. Catherine de. Zegher. Ocean flowers: impressions from nature. New York: Drawing Center, 2004. [7] L. Powell, (1991). Cyanotype - color it blue. PSA Journal, 57(6), 20+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA10888373&v=2.1&u=marylhuniv&it=r&p=AONE&sw=w&asid=883d1f4a640681052e83afdaffc8f9db. [8] Armstrong, Carol, and M. Catherine de. Zegher. Ocean flowers: impressions from nature. New York: Drawing Center, 2004.