“You don’t take a photograph, you ask, quietly, to borrow it.” -Author Unknown

You are exposed to thousands of images everyday. They scroll in front of our eyes on Facebook, Pinterest, billboards and more. There mode of existence is your computer, phone, car: essentially technology. This new age of technology comes with an over-saturation of images and easy access. In this blog I too contribute to plethora of images being produced. It is this trend that has offered support for a sub category of images marked rephotography.

Rephotographing historical sites or even other artist’s work has been a highlighted theme in the contemporary art world. A peaked interest has been found more recently in the heavy saturation of online images.

Are these advances in technology allowing for more taking rather than making of images?

Since the beginnings of photography we have been making photographs like other photographs. This is a normal process for all art forms, the difference in our discussion comes with understanding emulating and imitating.

The re-photography category is marked by imitation, not emulation. A copy of what is already done. Currently, we find it irresistible to click that ‘share’ button or to ‘re-pin’ that image of Grumpy Cat or Lil Bub. The world wide web, specifically social media, is filling that insatiable need to look and share and make it our own to tell.

For photographers it is the same appetite that spurs this subcategory on. We want to re-take images made by famous photographers, or even images found on Pintrest.

Where is the line drawn for originality, plagiarism and ‘your images’? Was it taken or made?

Several well noted photographers proudly take their place in the roots of this category. The first inklings of this started with re-photographing historical sites, and monuments around the country in about 1970. The re-photographic survey project was an idea conceived by Mark Klett, Ellen Manchester and JoAnn Verburg. [1] The project was called Second View, which was a three year effort to re-photograph the locations of previous government survey project, that were taken in the late 19th century (Fig. 1).

The effort was expanded throughout the years to include even more photographers and the rediscovery was remarkable. Mark Klett said “Sometimes the absence of change is the most salient.” [2] In replicating the images taken by photographers such as Timothy O’ Sullivan and Alexander Gardner, they learned about the aesthetic choices made years ago, and while restricted by composition they reveal instead the stunning and subtle variations in the landscape. The project played off of photography capturing a moment in time, it is the time lapse itself that is the most elegant feature of these photographs.[3]

Figure 1. From Second View. Left: William Henry Jackson,1873 “Moraines on Clear Creek, Valley of the Arkansas, Colorado.” [U.S. Geological Survey] Right: Mark Klett and JoAnn Verburg for the Rephotographic Survey Project, 1977, “Clear Creek Reservoir, Colorado.”

Both a Document and a Picture

In Paul Berger’s essay Doubling: This Then That, he discusses the importance of a photograph to have a type of “understanding” beyond that of words or book knowledge. He says “This duality is fundamental to our understanding of photography. As an image, the photograph can be both document and picture, artifact and art, visual map and carrier of cultural meaning.” [4] Every picture sits on a scale between these things, while some may be extreme, the obvious importance of re-photographing images was vital for Berger.

We may not be able to repeat the past, but we certainly can re-examine it, and that is exactly what the re-photographic survey project was doing. In fact, it did not stop with Second View. Third View, Second Sights is a re-photographic project that continued this same idea, and was done in 2004.

For Those Who Dare

While historical images were being re-done continuously, famous photographer Sherrie Levine broke from the mold with a daring move. In 1936 Walker Evans photographed the Burroughs, a family of sharecroppers in the depression area located in Alabama.

In 1979 Sherrie Levine re-photographed Walker Evans photographs from the exhibition catalogue “First and Last”. This was a gutsy move for a woman to re-claim the images of famous photographer Walker Evans. Through doing this she sends a gesture towards appropriation, while seemingly squelching every “creative” act that can be taken with photography.

Her images were shown in a gallery, which at that time also questioned the copyright laws and the highly enthroned respect for historical and documentary images.

She questions authorship and originality, the paradox is that the images she took of Walker Evans were released and could be copied and reproduced, however her re-photographs are protected by copyright. [5] Look below, cam you see the difference? (Fig.2)

Firgure2. On Left: Walker Evans, Allie Mea Burroughs, photographic print, 1935-36, Library of Congress. On Right: Sherrie Levine, Untitled [After Walker Evans, 1981.

Thank God for Google…Right?

Consequently, this was carried even further by Michael Mandiberg in 2001. He scanned these images and created afterwalkerevans.com and aftersherrielevine.com to facilitate a commentary on how we know information in this burgeoning digital age. He was able to do this with Sherrie Levine’s images because he attached the copyright laws, and renamed the images with the URL.

A more contemporary example of this expanding genre of re-photography can be found with Doug Rickard and Matthew Jensen. Both of these photographers are taking advantage not of prints like the predecessors of this genre, but instead of the online plethora of images available to us.

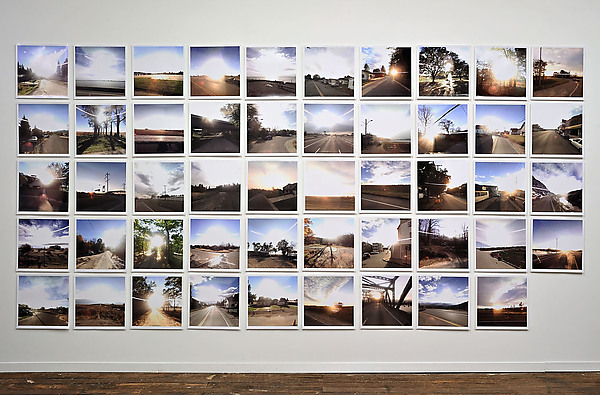

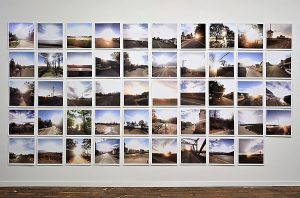

Figure 3. Matthew Jensen, 49 States, 35.6cmx35.6cm (14x14in ea), photographs, 2008-9, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY.

Figure 4. Doug Rickard, #29.942566, New Orleans, LA., photograph, 2008-9 Museum of Modern Art, NY

Figure 5. Doug Rickard, #39.259736, Baltimore, MD. 2008, 2011, photograph, Museum of Modern Art, NY.

Doug Rickard is an American born photographer who lives in Sacramento California. He received his Bachelors of Art in 1994 at the University of California. Doug had a large exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. His show was part of the “New Photography of 2011”.

This piece above (Fig.4 ) is titled #29.942566, New Orleans, LA. 2008. 2009. The title refers to a Google map URL code and the location and date it was taken. The composition of this photograph is in a panoramic view with a depth that is nicely considered by the artist as he composed this photograph. This is one image in a series of 22 photographs titled “New American Picture.”

Doug’s work certainly is unique. He assembled his images using Google street maps to find places where unemployment was high and education was at a minimum. He used these Google pictures that have snapped every street in the area, removed the water mark for Google and manipulated the images into panoramic views, then took a digital photograph of them and put together a series that has people talking not only about expanding the bounds of digital manipulation (Fig.5), but according to the Museum Of Modern Art in New York “ [it is a]… comment on poverty and racial equity in the United States, the bounty of images on the web, and issues of personal privacy.” [6]

The entire series takes a documentation approach, similar to the historical photographs we looked at earlier, however, they instill a sense of artistic style and take up a contemporary possibility from a new source.

There is a surreal and haunting felling to the images that are hyper exposed with bright vivid pools of color. People and figures are isolated and frozen in time. The roughness of the landscape and environment alerts viewers to the subjects and the areas current demise.

Rickard created a new way to approach the landscape that is in the world around us by using images that are mass produced and spread across the internet. Along with this, his use of digitalizing everything in his process gives him his own niche, especially among re-photographers.

He is not stealing the google paparazzi’s work, he is simply using the resources provided to him. Also his technique of reconfiguring and then reshooting the image creates a gap. Melony Bravmann, a highly educated writer for the Art Practical says “Re-photographing further removes the image from its original context; the gap between viewer and subject—the voyeuristic divide—is widened.” [7]

In a review done by Carman Winant at Stephan Writz Gallery during his show there, she says “In seeking out and uncovering these accidental American portraits, Rickard has highlighted the distinct invisibility of poverty, as well as the inherent political implications of mapping itself.” [8]

The images capture a reality, and a supposedly hidden world that is yet so accessible from your very computer. The reality is the iconic part of this artists work. The decay not only of a city but of a people is not something that usually greets the viewers eyes when gallery hopping.

Another angle the artist took was not having any contact with the subjects or the places. He took the ultimate road trip sitting at home on his computer in California, granted it took 10 months of sitting there, but the end result is worth it. Unlike the survey project he did not work in the field of immediate reality, but a digital reality.

Matthew Jensen is an up and coming photographer who recently had a show in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was a School of Fine Arts graduate with his MFA in 2008. Although he is a native from Killingly Connecticut, he is currently teaching digital imaging at The New School in Greenwich Village NY.

His series called 49 States, is very similar to Rickard because he too virtually traveled through Google earth images where he chose one image from each of the forty-nine states covered by this street view. [9] The result was very different from Rickard’s images.

He digitally altered them as well, but all of them have to do with sun flare and light in the images. These are not presenting an American portrait, but instead are highlighting the selective choices that an artist makes when composing an image- even if they did not photograph it immediately.

This is a visually stunning array of images that took a rigorous effort to discover, frame, highlight, edit and then finish in a final work. Jensen’s is aesthetically and thoughtfully addressing the way in which digital technology is affecting the world we experience. [10]

Ethics and All That

This continuous reoccurrence of rephotography is bringing several hot topics to the table; the ethical issues of originality and stealing vs. appropriating.

For the early rephotographers reasons for re-taking the images seems justified for a historical context, there is a very clear line of appropriation to a degree that can be explained in a conscious way. Also the original artists of the survey images receive credit. This sort of initial rephotography doesn’t cross the line of stealing, and even the originality is not embedded in the content or composition of the images but instead in the concept or re-discovery that goes hand in hand with re-photography.

In the case of Sherrie Levine, she took part in a sort of re-photography that made this genre of work a highly tumultuous area in terms of where the line should be drawn. The images were a commentary on this very issue of stealing and originality, which sparked a flame in the art world. These images are literally an image of an image. A copy of a copy was then made when they were placed on the internet.

The contemporary photographers Jensen and Rickard followed closely behind Levine in the appropriating of Google earth images.

The reason that these images can be called art, and can be individual is reliant on the boundaries that have been pushed before in the art world as well as the technological age making everything a much more accessible venue for art.

It is these social and even political occurrences in our time that have made this a possibility for not only photography, but art. They are art because the idea is genius- it has built a concept regarding what can be used for art.

In our current times, when social practice art and performance art has all been accepted into the art realm the world of art is not confined and in this situation it seems obvious that re-photography would occupy a space in the art scene.

It is the idea behind the work in the case for Levine, Rickard and Jensen. In many cases the idea is also to spark this very commentary on the work. Also it is to push outside of the confines of photography and embrace a respect for other photographers.

It is a avant-garde way of appropriating, and the originality in the message is not necessarily in the image itself, but in the concept and commentary.

All images are made. There is no question about this, but what is most fundamental about photography, specifically this wide ranged category is the process.

In other words, which comes first, the taking or the making. In the case of re-photography the taking comes first and the making comes second.

The originality of the image has already been done, but the originality of the concept is being re-done by re-photographers for the purpose of re-discovery.

Appendix:

This paper was written several years ago while attending Marylhurst Univeristy for a Photo History course with the worlds best teacher Darcy Edgar. Yet, as I read over it again it still holds poignancy in a world that is producing photographs by the billions. This is especially important to consider when creating images on your phone- when abundance can seem meaningful but perhaps is not or when re-creating an idea on social media.

What do you guys think about Levine? Rickard? Taken or Made? The idea of “re-photography”?

Bibliography Adams, Robert. Turning back. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2005. Bravmann, Melony. "A New American Picture | by Melony Bravmann | Art Practical."Art Practical. http://www.artpractical.com/shotgun_review/a_new_american_picture/ (accessed March 1, 2013). "Collection Online-Sherrie Levine." Guggenheim Museum. http://www.guggenheim.org/new-york/collections/collection-online/show-full/bio/?artist_name=Sherrie%20Levine (accessed March 1, 2013). Huddleston, John. Killing ground: photographs of the Civil War and the changing American landscape. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. Jensen, Matthew . "Jensen Projects." Jensen Projects. http://www.jensen-projects.com/ (accessed March 1, 2013). Klett, Mark. Third views, second sights: a rephotographic survey of the American West.1st ed. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of NM Press [u.a.], 2004. Klett, Mark, Ellen Manchester, and JoAnn Verburg. Second view: the Rephotographic Survey Project. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984. Mandiberg, Micheal. "AfterWalkerEvans.com." AfterWalkerEvans.com.http://www.afterwalkerevans.com/ (accessed March 1, 2013). "MoMA | New Photography 2011 | Doug Rickard." MoMA | The Museum of Modern Art. N.p., n.d. <http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/newphotography/doug-rickard/>. (accessed March 1, 2013) "The Metropolitan Museum of Art - The 49 States." The Metropolitan Museum of Art- Home. http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/190046296 (accessed March 1, 2013). Wallis, Brian. Art after modernism: rethinking representation. New York: NewMuseum of Contemporary Art ;, 1984. Winant, Carmen. "Doug Rickard @ Stephen Wirtz | Squarecylinder.com – ArtReviews | Art Museums | Art Gallery Listings Northern California." Squarecylinder.com – Art Reviews | Art Museums | Art Gallery Listings Northern California. http://www.squarecylinder.com/2011/05/doug-rickard-stephen-wirtz/ (accessed March 1, 2013).